Lucy Annie Kemp (her real name – it appears on her birth certificate – although she later claimed her middle name was Margaret) was born on 15 July 1885. Her father was a Blue Marine – a member of the Royal Marine Artillery, who wore blue uniforms rather than the more familiar red worn by Marines in general.

Robert Harry Kemp was about 27 when his daughter was born. He had married Lizzie Joslin in Portsmouth the year before.1 Robert (who seems to have been known as Harry as a child, although his wife called him Bob) was stationed at Eastney Barracks, but both he and Lizzie were from Essex. Their families lived a few doors apart in Hall Road Terrace, Heybridge, near Maldon.2

At the time of Lucy’s birth, the couple were living at 4 Cambridge Terrace, Eastney, close to the barracks.3 How long they remained there is not known. However, the evidence suggests that within a few years Robert and Lizzie’s marriage was to become distinctly shaky. Letters written by Lizzie to her sister Alice in Maldon suggest Robert was liable to drunkenness, neglect of the child and possibly even violence. In 1891, Lizzie and Lucy were living on their own in a house in Hall Road Terrace, the implication being that Lizzie had split up with Robert.

The split was only temporary, however: by 1894, Lizzie and Lucy were back in Eastney, this time living at 12 Newton Terrace (in Eastney Road). Letters written from there indicate that Lizzie was succumbing to an illness that would prove to be fatal. She died there, probably of tuberculosis, on 25 May 1894, when Lucy was just 8 years old.4

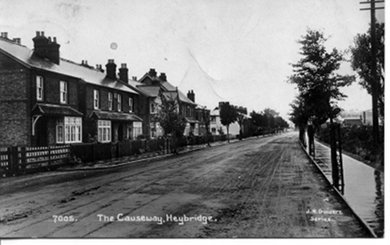

Although there is little documentation of what happened to Lucy after her mother’s death, it is clear that she didn’t remain with her father for long. She almost certainly moved back to Maldon, to live with her aunt and uncle, Alice and Asa Osborn, at number 84 The Causeway.

Alice was Lizzie’s younger sister, and apparently a formidable woman with strong views on everything. Her husband Asa, who had lodged with Alice and Lizzie’s family in the 1880s when he started work for Bentalls ironworks in Heybridge as a clerk,5 was a mild mannered, kindly man. They never had children, but both were pillars of the local Strict Baptist chapel. Alice in particular took a dim view of adherents of other religions, including the Anglicans in their ‘steeple houses’ and, worse, Roman Catholics. But even worse than Catholics were the ‘General’ Baptists. ‘If there’s one hell lower than another, they old generals’ll be in it,’ Alice would say, looking out of her parlour window on Sundays as members of this lower order of humanity passed by on their way up the Causeway to their own chapel at the Fullbridge.

What Aunt Alice thought about Robert Kemp is not recorded, but her thoughts are unlikely to have been kind ones. When his daughter returned to Essex, Robert stayed on in Portsmouth – although not as a member of the Royal Marine Artillery: he was discharged at some point during the 1890s. (In 1894 he seems to have been working as a scene shifter in a local theatre.6 ) In 1896, he had another daughter, Lilian, with Ellen Wood, to whom he wasn’t married. In fact Ellen was almost certainly still married herself, to Alfred Wood, with whom she had already had three other children. The 1901 census shows Ellen Wood as a boarder in Robert’s home, while their daughter Lillian (sic) is shown as Robert’s daughter.7 They were living at 8 Newton Terrace, just along from number 12, where Lizzie had died seven years before.

Lilian was born on 3 September 1896. There is no evidence that she ever met her half-sister Lucy, or that either even knew of the other’s existence. However, much later, in the 1930s, the sisters lived within about half a mile of each other in South London. Lilian married William Chrisfield in 1924; she died on the last day of 1966 in London. She had two daughters – one of them, Doris Wood, was born in 1919, the other, Elizabeth Chrisfield, was born in 1924. They married two Canadian brothers during the Second World War and later emigrated with them to British Columbia, where their descendants still live.

Lucy, meanwhile, seems not to have stayed in Essex very long. By 1901 she was working as a servant for a family in Tulse Hill, London.8 Nothing is known of what she did over the next decade, but on 15 January 1910 she had a son, John Edmund – usually known as Ted. Lucy gave her name on the birth certificate as Lucille. The name of his father is left blank, but in later life Lucy claimed that the boy’s father had been an Indian doctor, who had gone back to India and been killed in a car crash.

For some years Ted was to live with Alice and Asa at 84 The Causeway.9 They seem to have treated him as though he were their own son. Strangely, locals in Maldon knew Ted as ‘Teddy Telianka’. The spelling of this last name is open to interpretation – it is spelt here more or less as pronounced. Perhaps it could colourably be claimed to be an Indian name, but if spelt ‘Teleanca’ it might equally be a Romanian one. It is a small clue, perhaps, to the identity of Ted’s father, but not one that seems likely to prove of much use.

At the time of Ted’s birth Lucy (or Lucille) gave her address as 189 High Holborn. The 1911 census shows her to be a boarder in the household of George Clark, at 53 Lambeth Road.10 The relationship of John Edmond (sic) Kemp to the head of the household is given as ‘son’, but this is much more likely to be an error in the completion of the census than an indication of the truth about Ted’s parentage.

Even more perplexingly, Lucy’s (or rather, once again, Lucille’s) place of birth is given as “Pretoria, S. A.” This is clearly a fiction, and hard to account for at this distance of time. It’s likely, though, that Lucy had developed an elaborate story to conceal the truth about Ted’s fatherless condition. She is described as married on the census form and had perhaps got a little carried away in developing a back story for herself, and probably also an explanation for the absence of her husband.

Some time between 1911 and 1923, Lucy met a man called Arthur Joseph Sarl. He came from an acting family, and (according to family legend) had been involved in the theatre business himself, working as a publicist for Sir Henry Irving at the Lyceum Theatre.11 In 1906 he had married Frances Annie Rice, the daughter of a cowman, in Coldharbour, Surrey. The couple had three children.

At the time Lucy met Arthur, again according to family legend, she was working as a barmaid in a Fleet Street pub, and he was a journalist. (Arthur Sarl in fact had a distinguished career in Fleet Street principally as a racing correspondent – he filled the shoes of Larry Lynx on The People for twenty years.)

In the 1920s, Lucy and Arthur had two children, Jane and John. Lucy did not own up to their questionable parentage on their birth certificates, however: in each case she cited ‘Arthur Kemp’ as the father, and gave her own maiden name as Joslin in one case and Osborn in the other.

The precise nature of the relationship between their parents is not clear. Their children apparently believed them to be married, and Arthur seems to have turned up periodically, if not reliably, at their family home in Clapham. The children told odd stories about their father returning home after work to find that they had moved to a new house, although it is not clear whether this was a result of Arthur’s absent mindedness (which seems to have been notable) or his disconnection from the rest of the family.

It seems to be the case that Arthur spent prolonged periods with his ‘second’ family, even apparently accompanying them on occasional family holidays to Maldon, where he seems to have been known to the locals. They would stay at the Mill Beach Hotel, some way along the sea wall from Heybridge Basin in the direction of Goldhanger. The hotel was owned by a relative of Lucy’s.

One such holiday took place on the brink of the Second World War, during the summer of 1939. Arthur apparently was constantly on the telephone to the newsroom of his paper, catching up on the latest developments in the international situation.12

After the beginning of serious hostilities in 1940 Lucy appears to have left London to keep her son safe from the German bombers. (Her daughter, Jane, was a member of the Women’s Land Army.) They moved temporarily to Maldon, but after being strafed by a German fighter while walking across a field decided it was just as dangerous to be in the country as the city and moved back to London. During the Blitz Lucy was apparently unperturbed by bombs falling all around her, but at the first sign of a thunderstorm she would hide in a cupboard and not reappear until it was over.

There is no indication of Arthur’s whereabouts during the war years. When he died, in 1946, it seems to have taken some months before Lucy and her children learned what had happened.

At some point in the post war years both Lucy and John moved back to the Maldon area permanently. Lucy’s daughter, Jane, had married a farmer in the West Country. John found work in the office of E H Bentall & Co. in Heybridge, probably as a result of his relationship to one of its most respected employees, his great uncle Asa Osborn. Lucy and John moved into bungalows on the sea wall at Mill Beach, close to the hotel. When John married, in 1957, Lucy was so reluctant to lose her son that she wore black to his wedding – although she and John’s wife Monica later became completely reconciled.

Lucy was a regular attender at St Mary’s Church at the Hythe, in Maldon, until her death. It is a High Anglican church, and this seems to have been her preference throughout her life. She did not mix a great deal with her (no doubt abundant) relatives in the district, however, possibly because she wanted to avoid the embarrassment of raising questions (among her own immediate family) about her origins: she maintained that her husband had been called Arthur Kemp, and that she herself had been a Joslin (or, sometimes, an Osborn). Her younger son continued to stick to this story, although he certainly knew it was untrue.

When John bought a large house, formerly the Wave pub in Heybridge, Lucy moved in with him and his family, which now included four children. She was very old by this time (it was 1968, the year before her death) but still very spirited, and always ready for a good argument. She tolerated her grandchildren stealing her brandy and cigarettes without complaint, however.

Lucy died in her sleep on the night of 15-16 December 1969 from a combination of ‘a. hypostatic pneumonia, b. cardiovascular accident [stroke], and c. arteriosclerosis’, according to the doctor’s certification: in other words, essentially, old age. She was 84 but, in what was probably a characteristic piece of obfuscation, she had maintained for years that she was born not in 1885 but in 1884, as the death certificate states. Lucy had maintained that she had no birth certificate. She said she had been born ‘on the strength’ at Eastney Barracks and that in those circumstances formalities such as birth certificates were not required. It was nonsense, of course, but the story – and perhaps a little fiction about her date of birth – effectively prevented her birth certificate from being traced until years after her death. Once again, she was almost certainly concerned only to maintain the veneer of respectability she had laid on to her family background through a number of departures from straightforward fact. Her birth certificate, had it been found, would have shown clearly that she was born a Kemp, and so was most unlikely to have acquired the name through marriage (another formality that she seems to have gone through her life without engaging in.)

It’s tempting to come up with a few concluding words to summarize the life of Lucy Kemp, to characterize her in some way or to evaluate her as a person – a ‘wife’, mother, grandmother or whatever. Such a summary would most obviously concentrate on the negatives in her personality, since that is what we have most documentary evidence of (for example the lies she told about her background).

But quite apart from the fact that no one really has any business passing judgements on the character of anyone else, to judge Lucy on the basis of the evidence given above would be absurd and one-dimensional. She was a strong-willed and resourceful woman with a wicked sense of humour and a clear idea of right and wrong (which may well have differed substantially from the accepted views about right and wrong that prevailed during her lifetime). Deceptions of one sort or another were no doubt forced on her by the social conditions of the 1910s and 1920s, but her lifestyle was not one that many people would find objectionable (or even exceptional) today. So rather than pass judgement on Lucy (who would not have tolerated anyone doing so while she was alive) it would be more appropriate to pass a severely censorious judgement on the hypocritical social mores of the Victorian era in which she grew up, and of the early 20th century when she had her children, that forced her to construct a series of alternative life histories for herself.

Acknowledgements: I am indebted to Adeline Maguire of British Columbia, and Robert Kemp, of Cornwall, for some of the information in this article.

- Register, Portsea Island July-August-September 1864, Vol. 2b p. 729. [↩]

- Public Record Office, 1881 Census, RG11/1777. [↩]

- The address is now in Highland Road. [↩]

- Lizzie’s death certificate gives the cause of death as phthisis – often, but not always, another name for tuberculosis – and indicated she had been suffering from it for the past 18 months. [↩]

- Public Record Office, 1881 census, RG11/1777. [↩]

- Letter from Lizzie Kemp to Alice Osborn, 20 February 1894. [↩]

- Public Record Office, 1911 census, RG13/989. [↩]

- Public Record Office, 1901 census, RG13/438. [↩]

- Will of Alice Osborn (date unknown). [↩]

- Public Record Office, 1911 census, RG14PN1964 RG78PN69 RD25 SD1 ED22 SN100. [↩]

- This has never been independently confirmed, however. [↩]

- Much of the information given here is taken from At The Wash Of Oysters, a book of sometimes semi-autobiographical short stories by John Kemp, Lucy’s second son, which was published in 1987, shortly before the author’s death. Although not admissible as hard evidence, it is probably a reasonably reliable indication at least of what John Kemp believed to be the truth about his parents. This is corroborated by reminiscences John Kemp shared with his family at other times, which fit with the general outline of the story in At The Wash Of Oysters. [↩]