FRANK PHILIP FISHER 1923 – 1943

FRANK PHILIP FISHER 1923 – 1943

“NO KNOWN GRAVE BUT THE SEA”

Frank Philip Fisher, a British Merchant Navy officer, was Killed in Action during the Second World War on 12 March 1943 off the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador after his ship, the Baron Kinnaird, was sunk by a German U Boat. He was 20 years old.

Frank Fisher (known to his family as Philip) was the son of Francis William Fisher and Norah Fisher, nee Duncan. He was the eldest of six children: the others were Joan, Basil, Barbara, Maurice and John. The family lived in Ipswich, Suffolk. He takes the name Philip from his mother’s brother, Philip Duncan. Philip, a Second Lieutenant in the 2nd/8th London Regiment, was Killed in Action 26 years before his nephew, on 30 October 1917, during the Battle of Passchendaele in the First World War, aged 26. The younger Philip’s mother would not allow him to join the Army in the Second World War for fear that he should be killed as his uncle had been. She believed that her son would be more likely to survive the war serving in the Merchant Navy.

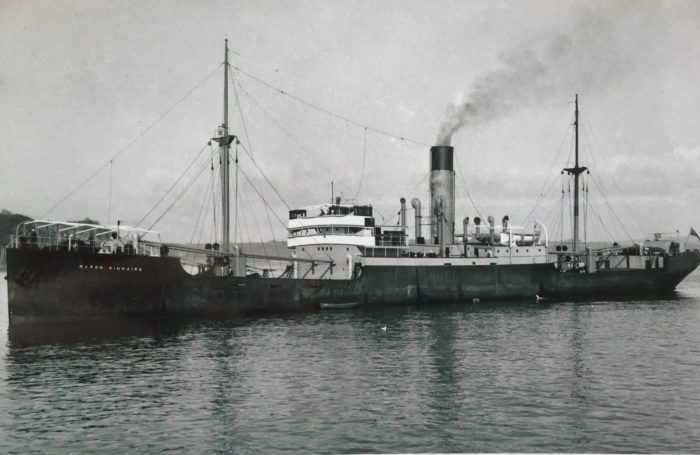

Philip was Second Radio Officer aboard the Baron Kinnaird. The Baron Kinnaird was a 3,355 ton merchant steam ship, built in 1927 by Napier & Miller in Glasgow. Her home port was Ardrossan and her owner H Hogarth & Sons Ltd of Glasgow.1

The company was founded by Hugh Hogarth of Ardrossan in 1870. It was a tramp ship company and became known as ‘The Baron Line’ and also ‘Hungry Hogarths’. The latter name due to a reputation for not feeding the crew very well. On the other hand the company maintained its entire fleet in operation and its crews fully employed throughout the depression. At the outbreak of WW1 there were 23 steamers in the fleet. Of these 14 were lost and 3 sold, while 7 others were acquired, leaving the company with 13 ships. In 1939 at the outbreak of WW2, Hogarth had 39 ships, one of the largest tramp fleets in the country. As a consequence the company suffered the high total of 20 losses. H Hogarth and Sons merged with Lyle Shipping Company in 1968 to form Scottish Ship Management Limited, formed in 1968. The company went out of business in 1986.2

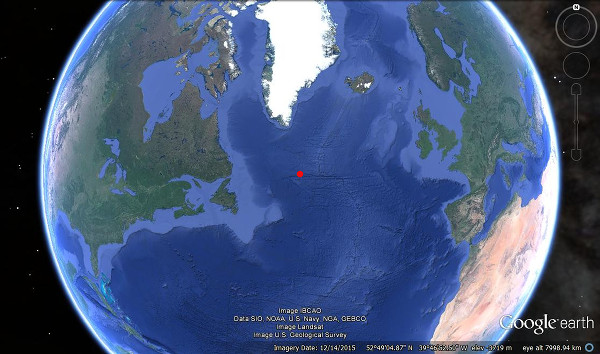

In early 1943 the Baron Kinnaird was bound from Middlesbrough to Macoris in the Dominican Republic with a ballast cargo. She made passage from Middlesborough via Loch Ewe in Scotland to Liverpool where she joined Convoy ON(S)169 under the command of Rear Admiral J Powell DSO. ON(S) 169 was a slow-moving convoy made up of 45 merchant ships (37 by some accounts) and 18 Royal Navy escorts. ON(S) stands for ‘outward, northbound, slow’ and was a prefix for convoys from the UK to North America. The Baron Kinnaird left Liverpool with the convoy on 22 February 1943.

On 27 – 28 February the convoy encountered a severe southwest storm and had to head into wind at slow speed. On 28 February the wind suddenly veered to the northwest, which put the ships in greater trouble and caused damage to some of them. From then until midday on 9 March a series of further storms passed over the convoy. In the heavy seas the ships repeatedly had to heave to. The average speed of the convoy was only 3.4 knots instead of 7 knots. On 6 March six ships lost contact with the convoy including the Baron Kinnaird, which thus became a lone straggler, outside the protection of the escort ships.3

There are conflicting accounts of the sinking of the Baron Kinnaird. The following, drawn from several of them, is considered to be close to the reality.

On 10 March the German submarine U-621, a part of U-Boat Wolfpack Raubgraf, made contact with the isolated Baron Kinnaird. The submarine reported her to be high out of the water and making slow progress at about 4 knots in a northwest swell, wind force 5 and rising. At 2250 hours, U-621 fired a spread of three torpedoes at the freighter, all of which missed. At 2259 hours the submarine fired a fourth torpedo which hit the ship but did not sink her. At 2317 hours the U-621 fired a further torpedo from the stern tube which again missed. The submarine dived to reload but was then unable to re-locate the ship, which had managed to proceed after being hit.

The U-621 re-established contact with the Baron Kinnaird at 1643 hours the next day, 11 March. At 1831 and 1912 hours U-621 fired two further torpedoes both of which missed. At 1917 hours the submarine fired a further torpedo which hit the ship a second time on port side aft in the area of the stern hold. Great holes were torn in both sides of the Baron Kinnaird but still she did not sink. The submarine then engaged with 20mm gunfire to try and set fire to the ship. At 1942 hours a further torpedo was fired which passed beneath the ship and at 2153 hours a second missed behind the stern. The U-boat remained nearby until the Baron Kinnaird finally sank at 1054 hours the next day, 12 March 1943.4

Of her complement of 42 men – the Master, 35 crew-members and six gunners – there were no survivors. The Master was Leslie Anderson, 43, and the youngest member of the crew was Bruce Beresford, a 17-year-old apprentice.5 Captain Anderson had been master of the Baron Cochrane, torpedoed only two months previously.6

There are inevitably many unanswered questions about the details of the Baron Kinnaird’s sinking and the fate of her crew. Having become detached from the convoy on 6 March but remaining afloat until six days later, 12 March, was it not possible for her to be given assistance and protected from the predations of U-621, or at least her crew rescued? The convoy escorts did in fact give assistance to another freighter that was torpedoed on 7 March, the Empire Light, and managed to recover her to harbour. But presumably the Baron Kinnaird could not be located or had strayed so far away from the convoy that to detach escorts to assist would have endangered the other ships. She was registered as missing from 7 March, after which presumably there was no radio contact between the Baron Kinnaird and the convoy. That is most likely to have been because of strict radio silence that would have been imposed across the whole convoy. Any electronic signal made by any ship could have been detected by the Germans and led the U boats straight to their prey. It may also have been because she had moved out of radio range or her equipment had gone down. Presumably the convoy commander had no knowledge of anything that happened to her after 7 March.

What became of the crew of the Baron Kinnaird, all of whom were lost? One report suggests that when U-621 made contact with the ship for the second time she seemed to be abandoned and drifting. How accurate that report is remains unclear. However it is possible that by this stage (presumably 11 March), the crew had abandoned ship. It is also possible that the crew remained aboard until some point before she finally sank, or went down with the ship. Whichever it was, the chances of surviving very long in small boats in a harsh and freezing Atlantic were slim. Their boats may have turned over in the swell and the storms and they’d have drowned. Otherwise they would have quickly died of hypothermia in small, exposed boats or, if drifting for long enough, starvation.

A final possibility is that some or all were killed by U-621. Some of course might have died when the two torpedoes struck. It is also possible that some died when U-621 raked their ship with 20 mm canon fire. This was reported by the captain as an effort to set the ship ablaze. It could also have been done to kill any crew members on board, although there is no indication of that.

Whatever the actual detail of the sinking of the Baron Kinnaird, the Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote, Supreme Commander of U Boats, was unhappy with U-621’s actions in that engagement, later judging them to be: “exemplary for future or similar cases how it should not be done”.7

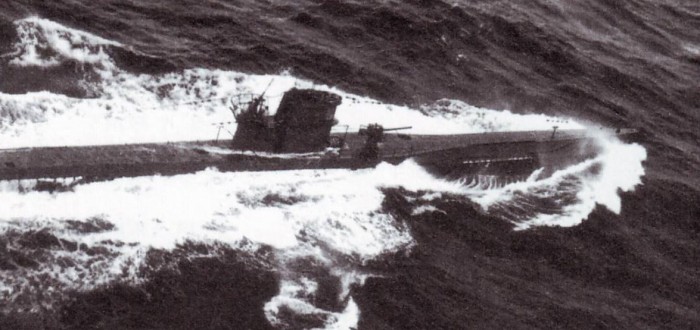

The U-621, a VIIC class submarine built by Blohm & Voss of Hamburg, launched on 19th March 1942 and commissioned on 7th May 1942,8 was part of the Kriegsmarine 9th U-boat Flotilla, operating from Brest. The U-621 had 5 torpedo tubes – 4 at the bows and one at the stern. The VIIC class was the workhorse of the German U Boat force in the Second World War from 1941 onwards. Perhaps the most famous VIIC submarine was the U-96, which is featured in the film ‘Das Boot’.9

The U-621 was commanded by Kapitanleutnant Max Kruschka, born 7th May 1919 in Schleswig, Germany, the holder of an Iron Cross 1st Class, Iron Cross 2nd Class and the German Cross in Gold. Prior to sinking the Baron Kinnaird, Kruschka, in command of U-621, had sunk two other ships, a Greek and a British vessel, both in December 1942.10

The U-621 had departed from Brest on 1st February 1943. Before sinking the Baron Kinnaird, the U-621 had been attacked on 24th February by Royal Canadian Air Force 5 Squadron, sustaining slight damage. On 21st March she was attacked both in the morning and the evening by aircraft from RAF 311 Squadron, sustaining no damage from either attack. The submarine returned to Brest on 23rd March after seven weeks on patrol.11

Later in 1943 the U-621 was converted to become one of the Kriegsmarine’s four flak submarines, surface escorts for attack U Boats operating from the French Atlantic bases, with greatly increased anti-aircraft firepower.12

In May 1944 Kapitanleutnant Kruschka handed over command of the vessel to Oberleutnant der See Hermann Stuckmann. In June 1944, Stuckmann and the U-621 fought against the Allied landings in Normandy and sunk two landing ships.

The U-621 was herself sunk with all hands by depth charges from Royal Canadian Navy destroyers HMCS Ottawa, HMCS Kootenay and HMCS Chaudiere on 18 August 1944 in the Bay of Biscay near La Rochelle.13 Her wreck is now designated as a war grave.14

Kapitanleutnant Kruschka survived the war and died on 12 April 1948 aboard the fishing vessel Senator Predohl.15

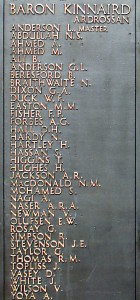

Philip Fisher and the crew of the Baron Kinnaird are remembered on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission Tower Hill Memorial. The Tower Hill Memorial commemorates men and women of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets who died in both World Wars and who have no known grave but the sea. It stands on the south side of the garden of Trinity Square, London, close to The Tower of London. The names of the crew of the Baron Kinnaird are inscribed on Panel 14 of the memorial.16

The Second World War extension to the First World War Tower Hill Memorial commemorates almost 24,000 casualties. It was designed by Sir Edward Maufe, with sculpture by Charles Wheeler. It was unveiled by Queen Elizabeth II on 5th November 1955.17

In wartime, Britain depended on civilian cargo ships to import food and raw materials, as well as transport soldiers overseas, and keep them supplied. The title ‘Merchant Navy’ was granted by King George V after the First World War to recognise the contribution made by merchant sailors.

Britain’s merchant fleet was the largest in the world during both world wars. In 1939 a third of the world’s merchant ships were British, and there were some 200,000 sailors. Many ‘British’ merchant seamen came from parts of the British Empire, such as India, Hong Kong and west African countries.18

During both world wars, Germany operated a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, or sinking merchant vessels on sight.

Losses were considerable in the early years of the war, reaching a peak in 1942. The heaviest losses were suffered in the Atlantic, where the Baron Kinnaird was sunk, but convoys making their way to Russia around the North Cape, and those supplying Malta in the Mediterranean were also particularly vulnerable to attack.

In all, 4,786 merchant ships were lost during the war with a total of 32,000 lives. More than one quarter of this total were lost in home waters.?? ??

Many tributes have been paid to the crucial role played by the Merchant Navy in winning the war. The following is taken from the website Canonesa, Convoy HX72 & U-10019 :

The historian John Keegan notes that:

“The 30,000 men of the British Merchant Navy who fell victim to the U-boats between 1939 and 1945, the majority drowned or killed by exposure on the cruel North Atlantic sea, were quite as certainly front-line warriors as the guardsmen and fighter pilots to whom they ferried the necessities of combat. Neither they nor their American, Dutch, Norwegian or Greek fellow mariners wore uniform and few have any memorial. The stood nevertheless between the Wehrmacht and the domination of the world”.

One seaman who served on one of the many Corvettes which escorted convoys throughout the war recalled that:

“We had great respect for the Merchant seamen. I think they were underestimated, especially now by the British public today, because they talk about the Battle of Britain. Granted the pilots did a marvellous, marvellous job, but when you stop and think, how did they get the fuel across to fly those planes, it was the Merchant seamen…..And, honestly, I think they’re the bravest men out, the Merchant Navy.”

Admiral Lord Mountevans, writing after the war, captured the atmosphere and danger of the convoys:

“Those of us who have escorted convoys in either of the great Wars can never forget the days and especially the nights spent in company with those slow-moving squadron of iron tramps – the wisps of smoke from their funnels, the phosphorescent wakes, the metallic clang of iron doors at the end of the night watches which told us that the Merchant Service firemen were coming up after four hours in the heated engine rooms, or boiler rooms, where they had run the gauntlet of torpedo or mine for perhaps half the years of the war. I remember so often thinking that those in the engine rooms, if they were torpedoed, would probably be drowned before they reached the engine room steps…”

In August 1941, when the outcome of the U-boat challenge to the convoy system was far from decided, Admiral Sir Percy Noble, Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches wrote that:

“For two hundred years, and more, these brave men, lacking the training and organisation that adapts their brothers in the Royal Navy so readily to the rigours of war, have, nevertheless, fashioned their own magnificent tradition. Day in, day out, night in, night out, they face to-day unflinchingly the dangers of the deep – the prowling U-boats. They know, these men, that the Battle of the Atlantic means wind and weather, cold and strain and fatigue, all in the face of a host of enemy craft above and below, awaiting the specific moment to send them to death. They have not even the mental relief of hoping for an enemy humane enough to rescue ; nor the certainty of finding safe and sound those people and those things they love when they return to homes, which may have been bombed in their absence. When the Battle of the Atlantic is won, as won it will be, it will be these men and those who have escorted them whom we shall have to thank.”

And indeed when the victory was won and the enemy vanquished the thanks of the nation were forthcoming. On 30 October 1945 the Houses of Parliament unanimously carried the following resolution expressing gratitude to the Merchant Navy on the victorious end of the war:

“That the thanks of this House be accorded to the officers and men of the Merchant Navy for the steadfastness with which they maintained our stocks of food and materials; for their services in transporting men and munitions to all battles over all the seas, and for the gallantry with which, through a civilian service, they met and fought the constant attacks of the enemy.”

The Right Honourable Alfred Barnes, Minister of War Transport said: “The Merchant Seaman never faltered. To him we owe our preservation and our very lives.”

Following many years of lobbying to bring about official recognition of the sacrifices made by merchant seafarers in two world wars and since, Merchant Navy Day became an official day of remembrance on 3 September 2000.20

- http://www.uboat.net [↩]

- http://www.benjidog.co.uk/allen/Baron%20Line.html [↩]

- Jurgen Rohwer, Critical Convoy Battles of World War II, Stackpole Books, 1977. [↩]

- http://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ships/2764.html [↩]

- http://www.uboat.net [↩]

- http://www.clydesite.co.uk/clydebuilt/viewship.asp?id=8399 [↩]

- http://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ships/2764.html [↩]

- http://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?14339 [↩]

- http://www.uboat.net [↩]

- http://www.uboat.net [↩]

- http://www.uboat.net [↩]

- http://www.uboat.net [↩]

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_submarine_U-621 [↩]

- http://www.uboat.net [↩]

- http://www.uboat.net [↩]

- http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/90002/TOWER%20HILL%20MEMORIAL [↩]

- http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/90002/TOWER%20HILL%20MEMORIAL [↩]

- http://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-merchant-navy [↩]

- http://homepage.ntlworld.com/annemariepurnell/can5.html [↩]

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merchant_Navy_(United_Kingdom) [↩]