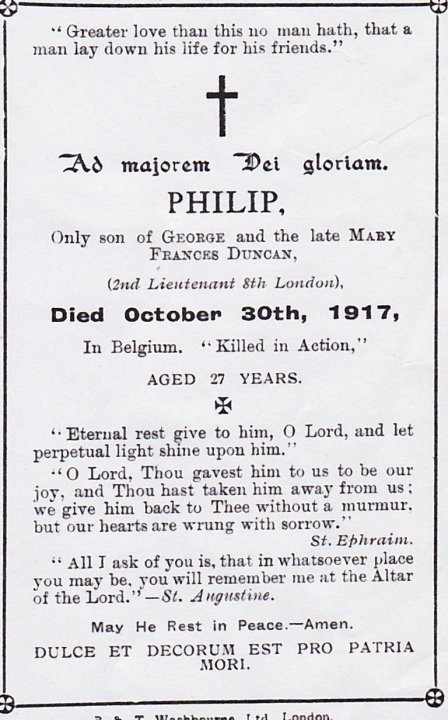

Second Lieutenant Philip Courtenay Duncan was Killed in Action near Poelcapelle, Belgium, during the Second Battle of Passchendaele on 30th October 1917 at the age of 26. He died leading his men in battle just 21 days after joining his battalion on the Western Front.

The Battle of Passchendaele took place near the city of Ypres in West Flanders between July and November 1917. British casualties are estimated at 300,000.

Philip was born in north London in December 1890, the only son of George and Mary Frances Duncan. He had two sisters, Edith (later Edith Richardson and then Edith Arbon) and Norah (later Norah Fisher). Mary died during their childhood and they were brought up by their father. ((According to Hugh Richardson, one of Edith’s sons and Philip’s nephew, who said that Mary died when Edith was 13.))

Prior to joining the Army Philip worked in a London bank, possibly in the Regent Street/Oxford Circus vicinity. ((According to Monica Kemp one of Edith’s daughters and Philip’s niece and Hugh Richardson.)) Edith also worked in a bank, the National Provincial and Union, in Regent Street. ((According to Hugh Richardson.))

Based on Philip’s initial Regimental Number, he joined the Army in November or December 1916. ((“Army Service Numbers 1881-1918”, website showing Artists Rifles regimental numbers. http://armyservicenumbers.blogspot.com/2009/01/28th-county-of-london-battalion-london.html)) He was older than the age group then being enlisted into the Services. (Since January 1916, when the Military Service Bill was introduced, British men were subject to compulsory conscription into the forces and were called up in groups based on various criteria. In 1916, 1.19 million men were enlisted into a force of nearly 4 million.) Philip had been in a reserved occupation and therefore not permitted to join the Army. ((According to Philip’s sister Edith, as told to Hugh Richardson.)) Thus we can assume that he joined voluntarily, and probably made considerable efforts to do so as it would likely have been difficult to leave a reserved occupation for any reason, even for military service.

After enlisting, Philip joined The Artists Rifles (formally, 28th [County of London] Battalion, The London Regiment). His training to become an infantry officer was probably at No 15 Officer Training Battalion at Hare Hall, Romford, Essex. ((This was the Artists Rifles’ officer training battalion, as shown on the Artists Rifles Association website, http://artistsriflesassociation.org/regiment-artists-rifles.htm.)) The initial service number he was allocated was 9720 and, after the Territorial Force was re-numbered starting in January 1917, he was given the number 763721. ((The Artists Rifles were allocated numbers within the range 760001 to 780000. See: ‘Army Service Numbers 1881-1918’ http://armyservicenumbers.blogspot.com/2009/01/28th-county-of-london-battalion-london.html)) Following his training with The Artists Rifles Philip was posted to the 2nd Battalion of The 8th (City of London) Battalion, The London Regiment, known as 2nd/8th Londons or The Post Office Rifles. ((Within the family there has been some confusion about Philip’s regiment. Military records and his gravestone show that he was an officer in the 2nd/8th Battalion The London Regiment (Post Office Rifles). According to Monica and Hugh, however, their mother had always maintained that Philip was killed serving with The Artists Rifles , despite the fact that his memorial card, which was presumably produced by his father, shows that he was a member of the ‘8th London’ (The Post Office Rifles).))

The Post Office Rifles was a Territorial Army regiment, formed in 1868 from volunteers. It has its origins in 1867 in the recruitment of 1,600 post office staff as special constables, in response to explosions in London and Manchester and disturbances elsewhere in the name of Irish independence. The regiment underwent several changes between its formation and the outbreak of the First World War. Although a link to the post office remained, by no means all of the soldiers that made up the regiment had themselves been employed by the Post Office. Early in the war the main part of the regiment was re-designated ‘The 1st/8th (County of London) Battalion The London Regiment (Post Office Rifles)’. This battalion went to fight in France in March 1915. ((http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post_Office_Rifles))

The 2nd/8th, Philip’s battalion, was formed in September 1914. The battalion remained in Britain until January 1917, when it crossed the Channel to join the fighting in France. ((‘Army Service Numbers 1881-1918’. http://armyservicenumbers.blogspot.com/2008/08/8th-city-of-london-bn-london-regiment.html))

Philip completed his training and was commissioned into the 8th Londons on 27th June 1917. ((Regimental Roll of Honour and War Record of The Artists Rifles, Third Edition, London: Howlett and Sons, 1922, page 295.)) He would probably have taken some leave and perhaps undergone further training or other duties in the UK before embarking for France. Based on accounts given in the book ‘Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War’ ((Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War, John Lewis-Stempel, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2010)) it is probable that Philip’s journey from home to join his battalion in France took him first to Waterloo station in London. He would have travelled from there by troop train to the south coast, probably Southampton or Folkestone, for embarkation on a troop ship. These were mostly commandeered paddle steamers or ‘crude and bare cargo ships’. The vessels crossed the channel with Royal Navy destroyers and airships alongside to protect against German U-boats. Most soldiers arrived at Havre or Boulogne although Rouen and Calais were also used.

After disembarking Philip probably spent the night in a transit camp outside the port. He would then have travelled by rail to Etaples, the British base depot. This was ‘a vast tented city for 100,000 men on a wasteland of dunes’. According to ‘Six Weeks’, the routine at Etaples was unchanging: ‘Breakfast was at 5.45. From 7 am to 7.30 pm officers and men alike were in the “bullring” training grounds… the finishing schools of the British infantry soldiers.’ They were given intensive instruction in ‘fist-and-boots unarmed combat, trench-digging, running uphill, bombing, bayonet-fighting and trench attacks’. After completing his training at Etaples, Philip would then have travelled by train to join his battalion.

We know from the war diary of 2nd/8th Londons, now published by the National Archives, ((The National Archives’ reference WO 95/3006/3, War Diary 1917-18 of 2/8 Bn London Regiment, 58 Division, 174 Brigade)) that Philip joined the battalion on 9th October 1917 at Landrethun, 8 miles south west of Calais and some 30 miles from Etaples. His arrival in the battalion is also referred to in the book ‘Post Office Rifles 8th Battalion City of London Regiment’, written by one of the battalion commanders, published 1919.

The 2nd/8th Londons had moved from France into Belgium towards the end of August 1917. Before Philip joined the battalion they took part in some minor fighting, and were bombarded by heavy artillery and gas shells, sustaining 100 casualties in the first four days alone. On the night of 19th-20th September the battalion took part in an attack on Wurst Farm Ridge, a major offensive.

Despite heavy opposition, the battalion succeeded in taking all of its objectives, though at a cost of 103 killed and 144 wounded. Killed and wounded totalled well over half of the battalion strength, which, according to the war diary, was 450 officers and men at the start of the battle. The action involved many deeds of heroism that characterized the fighting spirit of the Post Office Rifles. One example being that of 2nd-Lieutenant Chancellor, who, shot through the lungs, continued to command his platoon until the last objective was taken. Then, when put on a stretcher, he crawled off, saying that he would be damned if he would leave his men, and remained with them.

2nd-Lieutenant Richardson, wounded in seven places, and 2nd-Lieutenant Mortimer, shot through the knees, also struggled on with their men until all objectives had been taken and consolidated. Sergeant Knight charged an enemy position and captured it single-handedly, showing no regard for his personal safety. He was awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest medal for gallantry, for “most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty during the operation against the enemy positions”. Thirty nine other soldiers in the battalion were also awarded gallantry medals for their actions during this battle.

After the battle, the battalion went to a rear area at Landrethun for rest and training. A battalion sports and assault-at-arms competition was held during this time.

The war diary shows that during the period at Landrethun, the battalion received reinforcements to replace the large number of men killed and wounded in the fighting at Wurst Farm. Philip was one of these; and 104 other ranks joined the 2nd/8th Londons with him on 9th October. A further 84 reinforcements joined the battalion two days later. Some of these may have been posted in from holding units, some returning to active service from hospital having been wounded, but most, like Philip, straight from training. Many of them would probably have been with him at the base depot at Etaples.

The 2nd/8th Londons’ war diaries give us an idea, in brief outline, of what happened from then on. On 20th October the battalion moved 60 miles eastwards to Poperinge in Belgium, just west of Ypres. The move would probably have been made by train, but could have been by lorry or bus. On 24th October the battalion moved 5 miles closer to the front-line, to Siege Camp near Elverdinge. This was a tented camp, two miles back from the front line, used by troops moving into and out of the front. Virtually every yard of this area behind the front was occupied by camps and horse lines, and according to the regimental history of 6th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment, which spent some time at Siege Camp during the same period, German planes were overhead, bombing every night. ((The History of the 6th (Service) Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment 1914 – 1919, F. G. Spring, 2008, ISBN 0955991404.)) A soldier from another regiment who was in Siege Camp around the same time wrote in his diary: ‘Hate Siege Camp worse every time I see the place. Always being shelled and bombed’. ((http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol071dh.html)) This was also Philip’s battalion’s experience: the war diary shows that the day after the 2nd/8th Londons arrived, three of their officers were wounded by bombs.

On the 26th the battalion moved forward to ‘Canal Bank Ypres’ – the front line. We don’t know whether they occupied a forward trench line directly facing the enemy, or a support trench position, just behind. Two days later, on 28th October, the Commanding Officer of 2nd/8th Londons issued orders for an attack against enemy strong points between the villages of Poelcapelle and Passchendaele as part of a major offensive.

Preparations for the attack began immediately, including re-organising fighting equipment. The men were required to wear leather jerkins and carry light battle order only into the attack. This consisted of rifle and bayonet, haversacks to be worn on the back, entrenching tool to be worn in front, one full water bottle, iron rations and mess tin. They were ordered to take only approximately half the normal battle load of ammunition, which for the rifleman was 50 rounds of .303 bullets, one grenade and one ground flare per man. No additional equipment was to be taken as they were to go into battle as lightly equipped as possible. Packs and all other ammo and equipment not required were centralized at Canal Bank to be moved to join up with them after the battle. Before leaving Canal Bank they painted a coloured X on their haversacks as recognition symbols – A Company red, B Company black, C Company yellow and D Company blue.

The following day, the 29th, the battalion left Canal Bank and marched the few miles to Kempton Park Camp, a similar set-up to Siege Camp but with huts. The hours at Kempton Park would have been spent checking weapons and equipment, filling water bottles, giving orders for the impending attack and rehearsing assault formations and techniques. The men may have been given a hot meal in the camp and perhaps had the time for a couple of hours rest and to write letters home. Around half of these men were newly arrived reinforcements to the battalion, and many of them, including Philip, would be contemplating going into battle for the first time in their lives. They would have been well aware that the last time the battalion conducted a similar operation, more than half were killed or wounded.

At 8 pm that evening, the 29th, the battalion marched from Kempton Park Camp to the assembly area for the attack. Their routes into the assembly area and then forward into the assault were marked by guides, tapes and coloured lamps. Although the distance was only about three miles, it took six hours to march over duckboard tracks from Kempton Park Camp to the assembly area. According to one account, the battalion was shelled by the enemy as they marched. The personal recollections of Arthur Borseberry, a soldier in the battalion, gives harrowing details of this march up before the battle. ‘The ground over which we had to pass was a quagmire, men were falling and slipping off the duckboards into the mire and sinking. The order was “keep moving, don’t stop. ‘ow about our comrades sinking in the mud Sergeant?” the call would go out, “so and so has fallen in.” He would be shot before he suffocated in the liquefied ooze. I cried a lot on that journey.’ ((Imperial War Museum Archives MISC 139/2165 Arthur Borseberry, quoted in “Londoners on the Western Front – The 58th (2/1st London) Division in the Great War”, David Martin, Pen & Sword, 2014.)) They were shooting their own men, out of mercy, rather than letting them drown in the mud.

The men arrived in the assembly area at 2 am and waited in that position for nearly four hours prior to attacking before dawn at 5.50 am. Between 3.00 and 4.30 am the troops came under fire from enemy machine guns and artillery, both high explosive and gas shells. ((“Londoners on the Western Front – The 58th (2/1st London) Division in the Great War”, David Martin, Pen & Sword, 2014.)) The battalion sustained 20 casualties before the attack began. According to the war diary there was a brilliant moon which made the move into the assembly area easier but also enabled the enemy to spot their movements and engage them with fire. The Commanding Officer of the battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Derviche-Jones, went around and spoke with the troops in the assembly area and found them to be ‘cheerful and in good condition’.

The war diary entry for 30th October reads: ‘The Battalion attacked SE of Poelcapelle at 5.50 am.’ The next war diary entry, on 31st, reads: ‘The Battalion was relieved on night 30th/31st and proceeded to Siege Camp. Casualties:- killed Captain PP Wheeldon, 2Lt PC Duncan, OR 34 [34 other ranks].’ It then goes on to list the wounded and missing.

The following is an account of the battle. It is taken from a history of the Post Office Rifles, written by one of the battalion commanders and published in 1919. ((“Post Office Rifles 8th Battalion City of London Regiment”, written by one of the battalion commanders, published Gale & Polden, 1919. Reprinted by Naval and Military Press, ISBN 1901623513.))

On October 28th a sudden order was given to the Battalion to attack, in co-operation with one company of the 2/6th [Londons], on the night of October 29th-30th, in order to support the main attack by the Canadians on Passchendaele Ridge. On this occasion the state of the ground was even worse than on September 20th [the Battle of Wurst Farm Ridge]; there had been heavy rains in the meantime, and the duck-board tracks were some hundreds of yards short of the outpost line. The ground was almost unknown, and there was practically no time for reconnaissances. The men were guided on to the assembly line by carefully screened coloured lamps placed to show the boundaries of each company’s front.

The objectives were Moray House, Papa Farm, Hinton Farm, and Cameron House, strong points lying between Poelcapelle and Passchendaele. From aeroplane photos the ground to be traversed seemed like a vast morass of mud and slime, as indeed it turned out to be. [One of these aeroplane photos is in the picture gallery linked to this page.] But little progress could be made. Men sank to their armpits in mud, and provided easy targets for the enemy. No support was forthcoming on the right. In spite of that, progress was made in the course of the day to about 500 yards, and outposts established, which, however, were ordered to be evacuated at night, except Nobles’ Farm, which had been captured by the 2/6th on the left.

The casualties were very severe: five officers killed (Captains Wheeldon and Barnett, and 2nd-Lieutenants Duncan, McAllister, and Barnes) and five wounded (Lieutenant Shapley, and 2nd-Lieutenants Finch, Tinsley, Peacock, and Booth); and of other ranks, 34 killed, 173 missing (all believed to have been killed or drowned), and 42 wounded. [The war diary had listed Captain Barnett and 2nd-Lieutenants McAllister and Barnes under wounded and missing.]

To illustrate the state of the ground, four men tried for two hours with ropes to extricate a comrade, and failed. Though no objectives of this Battalion were taken, the main purpose of the attack was achieved, in that this lone Battalion, struggling against an even more implacable enemy than the Boches, drew so much artillery and machine-gun fire as to materially relieve the main attack on the Passchendaele Ridge.

The 2nd/8th Londons’ war diary provides further details of the battle in which Philip Duncan fell. These have been extracted from Operation Orders No 17, Administrative Instructions dated 28th October 1917 and Preliminary Report on Operations of 30th October 1917, dated 31st October, copies of which form part of the war diary. ((The National Archives’ reference WO 95/3006/3, War Diary 1917-18 of 2/8 Bn London Regiment, 58 Division, 174 Brigade))

The Corps Artillery bombarded the enemy trenches for 48 hours before the attack. A few minutes before the attack began an artillery and machine gun barrage was fired at the enemy positions and 200 yards in front of the advancing troops. The barrage moved forward as the troops advanced. This artillery and machine gun fire however proved insufficient to keep the Germans’ heads down and did not stop them from firing machine guns and rifles at the advancing troops as they left the assembly area and continued the attack.

The Commanding Officer reported: ‘our barrage did not affect them’. He wrote: ‘All the men who were in the Action of the 30th September [Wurst Farm] as well as in this Action say that the barrage was weak and nothing like so good as on the 30th September’. He reported that the enemy artillery barrage against 2nd/8th Londons as they moved into the attack was also ‘a weak barrage but caused some casualties’.

As the 2nd/8th Londons moved forward from the assembly area, ‘in all places men were up to their knees, thighs or waists [in mud] in every step taken’. ‘No man could get a fair foothold anywhere and most were slipping over into shell holes. By the greatest determination positions [objectives] were reached… by a few, very few men.’ ‘The mud was thick and sticky and the men were exhausted before advancing 100 yards.’

Running or any fast movement through the mud was impossible, and the slow-moving soldiers were not difficult for the enemy to hit. ‘The ground was the enemy and gave the Boche easy targets whenever a man stood up.’ Some soldiers managed to get forward by crawling through the mud on all fours. Even crawling, as the men moved many of them were hit by machine gun and rifle fire. ‘If they advanced upright they were an easy target, if on all fours the men were exhausted in a few minutes.’ ‘Where sections [unit of 8 –10 men] kept together the whole section was hit.’

Most communication at this time was by runner. Control and coordination of the attack was made more difficult because of the problems runners and signalers had in crossing the battlefield. Nearly all the company signalers were hit. ‘The first message was brought back [to Battalion Headquarters] by a man crawling through the mud the whole way on all fours – he was utterly exhausted and many hours late.’

Rifles were wrapped in canvas or cloth sleeves to prevent mud jamming them and blocking up the barrel. Some of the troops unwrapped their rifles when the attack began to provide covering fire as their comrades advanced, but they became useless after the first fifty yards. The remainder kept their rifles wrapped until reaching their objectives and consequently were unable to fire them as they moved forward. All covered rifles were useless within 10 minutes of being uncovered.

The following is an account of the battle by a rifleman in the 2nd/8th Battalion. ((Quoted in “Terriers in the Trenches – Post Office Rifles at War 1914-1918”, Charles Messenger, Picton Publishing, 1982.))

Going up the line we first went a considerable distance over a duckboard track which was laid over the mud and shell holes. These tracks took the place of the communication trenches on other sectors of the front. The tracks were visible to the Germans who held the higher ground on Passchendaele Ridge; so we were constantly shelled.

At the end of the duckboard track we found that the ground sloped down a little and then started to rise up towards the top of Passchendaele Ridge. After great difficulty in traversing the waterlogged ground we arrived at a point where a white tape had been laid for us to assemble on. As we were in a very exposed position we had to get down despite the mud and water. I and several others lay on our backs on the inside edge of a shell hole and were soon soaking wet.

At 6.00 am exactly our barrage started and unfortunately opened up right on top of us knocking out many of our men. [It is possible the writer of this account mistook enemy artillery fire for their own artillery fire, as no other account of this action mentions being hit by their own barrage.] However, in the dim light we attempted to advance but were caught in machine gun fire and we became literally stuck in the mud.

We were able to get a little cover on the edge of some shell holes and here we were pinned down as the slightest movement brought enemy fire. The day seemed endless. All day there was intermittent shell fire and we were showered with water and mud when one exploded near. Several more of our chaps who moved were picked off by snipers. The dead and wounded lay all around us and about a hundred yards to our rear was a concrete ‘Pill Box’ which had been captured previously. This was being used as a first aid post and during the afternoon two stretcher bearers were moving about outside. They carried a Red Cross flag and were trying to help the wounded. I remember being surprised at the fact that they were not fired on by the Germans. Another incident I recall was when I asked a small man near me who he was and I learned he was the CO of A Company. I did not know that he was an officer as he wore a Rifleman’s uniform for the attack. As the day wore on we became desperately hungry and our rations were in our haversacks which were strapped on our backs and our fingers were numbed with the cold. Also we couldn’t make much movement to get them.

Just as it was getting dusk one of my companions by the name of Warren said he couldn’t stand any more of waiting. So he attempted to get up and was immediately shot dead by a sniper.

We had gone into the line solely for the attack which we were in no position to pursue: so as soon as it got dark, a few survivors including myself, started making some attempt to get back towards the duckboard track. My legs were numb, so as I couldn’t stand, I began to crawl and my arms sunk into the mud up to my armpits and I lost my rifle in the mud. I felt like a fly on a flypaper, and I began to wonder if I should ever get away.

I personally did not see anyone drowned in a shell hole, but I can quite believe this did happen, especially if wounded and helpless. After a great struggle we eventually got back as far as the Pill Box. The scene here was terrible. The dead and dying were all around it and we lay exhausted among them. After a time we were able to unfasten each other’s haversacks and get some food. This helped a lot and we at last were able to get to the duckboard track where eventually we reached the end and found some mule drawn limbers waiting to take the survivors. It was a terrible rough ride. First War limbers were but boxes on iron-shod wheels without springs and we traversed a road made up of tree trunks. A Padre who was in the same limber as me said he couldn’t stand it and got out, falling onto the road. I never knew what became of him.

I lost the use of my legs for three days.

The historian and military writer Charles Messenger says, in his history of the 2nd/8th Londons in the Great War: ‘It had been a disaster. Initially the battalion had managed to advance some 500 yards and had managed to establish some sort of outpost line, but this was ordered to be abandoned during the night. Five officers were killed, and a further five wounded. Of the men, thirty-four were definitely known killed and forty-two wounded, but staggeringly no less than 173 were posted as missing. Drowned in shell holes, wounded and died of exposure, killed and their bodies torn into unrecognisable fragments by shell fire, were some of the reasons why they could not be traced. But even more noteworthy is the fact that this battalion, which five weeks previously should have suffered over fifty per cent casualties, should attack again and lose the same proportion of its strength, and still afterwards remain effective. Even to be told a few days later by their Divisional Commander that they had not been expected to capture their objectives and had merely been used to draw fire off the Canadians did not totally extinguish their morale.’ ((“Terriers in the Trenches – Post Office Rifles at War 1914-1918”, Charles Messenger, Picton Publishing, 1982.))

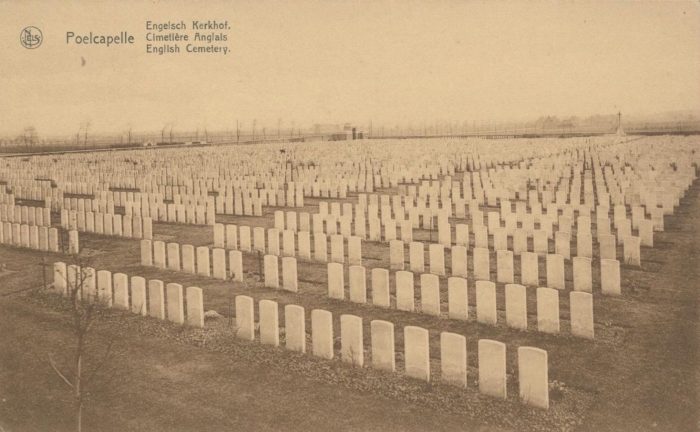

Philip Duncan would have been commanding a rifle platoon of around 30 men at the start of this battle. We do not know at what point he was killed or whether he died from enemy machine gun, rifle or artillery fire, or from drowning in the mud. It is probable that his body was recovered from the battlefield on the 30th or 31st and he would then have been given a temporary burial somewhere nearby. It is likely that some members of his battalion were present at the burial and it may be that he was buried by soldiers of the 2nd/8th Londons. In 1919, Philip’s remains were exhumed from his temporary grave and brought to Poelcapelle British Military Cemetery, Langemark, Belgium, where he now rests alongside many of the other men of 2nd/8th Londons killed with him on 30th October 1917.

All of the remains in Poelcapelle were brought in from the surrounding battlefields and a number of smaller cemeteries in the area. The great majority of the graves date from the last five months of 1917, and in particular October, but some plots contain many graves of 1914 and 1915. There are 7,479 Commonwealth servicemen of the First World War buried or commemorated in Poelcapelle British Cemetery. 6,230 of the burials are unidentified but special memorials commemorate 8 casualties known or believed to be buried among them. Other special memorials commemorate 24 servicemen buried by the Germans in other burial grounds in the area whose graves could not be located. There is also one burial of the Second World War within the cemetery. Among those buried in the cemetery is Private John Condon of the Royal Irish Regiment, who at 14 is thought to be the youngest battle casualty of the First World War (although there is now some dispute about whether these are in fact his remains).

Philip’s grave is plot number XXXVIII.A.3 at Poelcapelle. A photograph of his gravestone, and other details, appear on the War Graves Photographic Project website. ((The War Graves Photographic Project, in association with The Commonwealth War Graves Commission website: http://twgpp.org/information.php?id=1244130.)) Philip’s niece, Monica Kemp, visited the grave in August 1996, 79 years after he was killed not far from the spot where he is buried. Her grandchildren, James and Jenny Christie and Anna Kemp, and her son, Richard Kemp, accompanied her.

The War Graves Commission record correctly lists Philip as the son of George H Duncan of 58 Claremont Rd, Highgate, London. But it also says he was the husband of Frances M Riley (formerly Duncan). Philip was not married although is believed to have become engaged before he left for the Western Front. ((According to Monica Kemp and Hugh Richardson. Hugh was told by his mother, Edith, that Philip was engaged shortly before he went overseas)). It is hardly surprising that there should be errors of this sort in the military burial records of a nation in which nearly 900,000 soldiers were killed between 1914 and 1918.

Although not the closest family link, it is worth mentioning that Philip’s cousin’s great uncle, Brigadier General (later Major General) Clifford Coffin, won the Victoria Cross while Commander of 25th Infantry Brigade on 31st July 1917 during the early stages of the Battle of Passchendaele. ((List of VC winners, RE Museum website. http://www.victoriacross.org.uk/ccroyeng.htm))

Philip’s name is recorded in the War Record of the Artists Rifles. ((Regimental Roll of Honour and War Record of The Artists Rifles, Third Edition, London: Howlett and Sons, 1922, page 23.)) His medal card ((National Archives Catalogue Reference WO 372/6.)), which survives at the National Archives at Kew, shows that he was awarded the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. He would not of course have received either before his death. His father should have received a letter from King George V, a bronze memorial plaque (nicknamed the “Death Penny”) and a scroll to commemorate his sacrifice for the nation.

After his death Philip’s father received a letter from his commanding officer in which he wrote that Philip was especially popular among the other officers in the battalion and the soldiers that he commanded, making a great impression in the short time he was with them. ((Monica Kemp and Hugh Richardson both remember seeing or hearing of this letter.))

Richard Kemp

2 January 2012

Updated on 25 May 2014 with new information from 2nd/8th Londons War Diary, recently published by National Archives.